Guest Writer: Mimoza

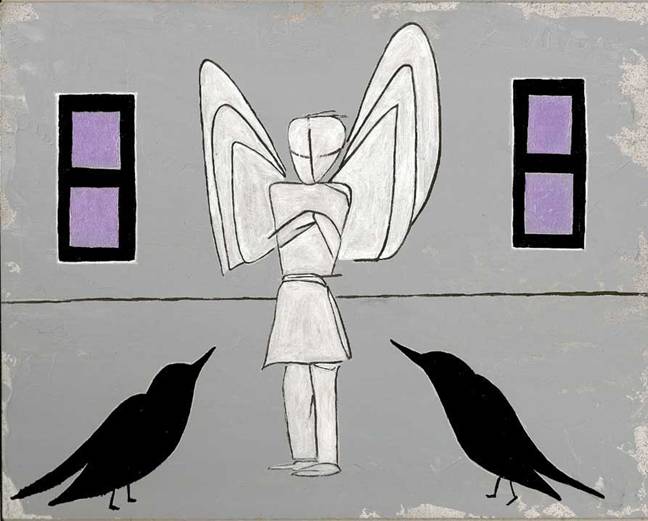

“You need two wings to fly. You should endeavor for your afterlife as much as you do for this world.” says my mother. Not occasionally, she perpetually says this. On every phone call a daily interrogation follows this bird metaphor: “You go to tarawih, don’t you? You know this is such a wonderful holy month, make good use of it. You don’t go to muqabla and I’m so worried for this.” So, I can’t help but feel my mother beside me instead of Allah during my prayers. Surely my dearest mother would never think that her daughter could turn into a person with two personalities when she dreamed for her to fly as a two-winged bird.

Year 1998-99. I started primary school in the oppressive period as the post-effects of February 28 spread over the country. My father was a civil servant in a state institution and we lived in one of the most secular neighborhoods of Ankara where most of the population were civil servants, soldiers and jurists. Every day my brother and I were warned over and over on our way to school (with my father of course because my mother wore hijab): “Listen. If anyone asks, we love Atatürk, okay? If your teacher asks you what you did in the weekend don’t tell him you went to take Quran lessons!” It was nonsense, but these cautions were actually useful. Our teacher asked about our lives at home every day in our highly educational school. Which party our parents vote for, what they do in New Year…? If we can recite the verses of Quran, who teaches us? We were made stand up and answer the inquiry one by one in class. It didn’t seem absurd to us as we were only children. We never wondered the intention of our teacher. To be honest I kind of began to like this game. I had one life at school and one at home. I would make the best of my imagination to create the stories that masked our religious life. Most of my friends had secular families, but I wouldn’t feel myself cast out because “we played tombola in New Year’s eve too! (My father would send us all to bed early that night)” and “we went to the beach in summer holiday too! (I was not allowed to wear swimsuit or bikini; my mother would put on capris under my swimsuit. We would look for isolated places to swim)”.

When I started middle school my parents thought they didn’t need to warn me anymore. But I had no intention to be out of the game yet. I was made myself accepted in my social circle as the person I had pretended to be so far. Being secular and Atatürkist then was an easy persona for a teenager which did not require any explanation. But things began to change after I started taking Quran lessons in summers. As I gradually felt more like I belonged to the secular persona game in my mind, my parents became more and more insistent on me being two-winged. My success at school wasn’t pleasing enough for them. I mustn’t have improved myself on one wing only. I must have achieved the same success at my religious education and realize their dreams of the perfect individual. Facing the inevitability of this obligation made my teenage traumas worse. Even in this situation I managed to convince my friends that I went ‘camping in the nature’ every summer (but I returned with no sunburns!) with my immense imagination. It was difficult but I was having fun. However, when I started high school and became aware of the fact that we were expected to behave more mature now, the games got harder and turned out as identity crisis. Our families were no longer religious or secular. We were religious or secular. If you were religious, the length of your skirt was below your knees, your shirt was buttoned all the way up, and you did not be friends with boys. If you were secular, you drank alcohol secretly, you had male friends, and you could come to school with short skirt. I, on the other hand, wore pants for all my high school years to avoid the skirt test, I unbuttoned the top button of my shirt before I walked into school, and hid my friendships with boys from my parents. Also, now there was the notion of ideology in our lives that we had to defend with everything we got. Surely it was the easiest way to play the Atatürkist persona in a high school where the teachers were Atatürkist. Shouting the slogans and going to Nazim Hikmet Cultural Centre was the fun part. But this time the ideology felt less a game and more real. The more I defended and learned it, the more I seemed to adopt the identity. My life was good at school, stormy at home. My parents didn’t like it at all. I was still sent to Quran lessons at summers, what I wore was being supervised, and my mother was trying to find religious friends for me. It was unbearable at some point. When I got the chance to go to university in Istanbul, I happily went for it without thinking. My parents didn’t let me loose there either, they didn’t allow me to stay at the dormitory because it was mixed, so they found me an apartment that belonged to a religious community they didn’t know well. To my luck it was not a strict place and I was very happy that I was no longer under the pressure of my parents. I was finally free (!). I got myself in a group of friends in the first year. I could live my life as a proper secular (!) now. But it was nothing like I had imagined.

I was disgusted by the drinking parties and explicit speaking of sexuality, I would often lose my interest and wander off to the distance while people around me were talking and laughing. The circle that I thought I belonged to for years didn’t look pleasant anymore. Meanwhile I had disagreements on religious matters with the community whose place I was staying in. But they didn’t consider me competent enough to talk on religious matters because I didn’t wear hijab and live my life like a religious person. Loneliness and depression were taking me slowly and I spent the whole year skipping classes, going to exams only, questioning who I was and where I belonged. Both my grades and friendships went terribly down in this solitude, and I isolated myself almost completely from my religion. I failed both in religion and study now. The two wings my mother thought she invested in for years were gone. After I got to the bottom where I could describe myself literally pathetic, I felt genuinely free for the first time. All these years I had never noticed that I was stuck between two identities because I was so worried about what my mother would think, if my father would get angry or if my teacher and friends would cast me out. I had never thought about what kind of life I truly wished to have.

I thought, read and wrote. Eventually I decided to wear hijab and become a Muslim anew from the beginning. I left the community house I lived in with this determination. My friends from the first year pretended they didn’t know me, my mother said “How can you find a job now (!)”, my father rejoiced quietly, one of the lecturers kicked me out of his class (because I wore the hijab); I, on the other hand, felt that I was my true self finally.

To be continued.

Yorum Ekle